The following courtesy of SN1/C Bob Reardon (44-47).

DISCLAIMER: ALL NAMES AND EVENTS WITHDRAWN FROM A 50+ YEAR OLD MEMORY BANK!

CORRECTIONS AND ADDITIONS WELCOMED

|

Comdr. A. A. Ovrom |

THE MANSFIELD STORY |

|---|

| Like so many other destroyers of our navy, the USS Mansfield has a distinguished record of loyal service that rivals that of any commissioned destroyer today. Her contributions to winning the war in the Pacific and to supporting our foreign policy in Chinese and Japanese waters in the long months that followed have been many. She has, in war and peace, discharged her duties faithfully and proved herself worthy of the flag she flies. Commissioned at Bath, Maine in April 1944, the USS Mansfield geared for war, passed through the Panama Canal in September of 1944 and steamed into the blue waters of the Pacific. Since that fateful day, she has neither navigated nor seen any other ocean. The historic Pacific alone has borne the weight of this super-destroyer. For almost three years, during the war and the turbulent months that followed, she covered the span of this mighty ocean, performing her duties in the traditional navy manner. The ship’s log tells an endless story of missions and adventures that carried the Mansfield from Ulithi, an island stronghold in the Western Pacific, to Leyte, Samar, and Luzon in support of the Philippine Landings, assistsing General McArthur in fulfilling his promise “I shall return”. While in this campaign, she steamed up and down the South China Sea in company with the famed “Luzon-Saigon Night Express”.Finishing her job here, the 728 moved on to lend a hand in the invasion and occupation of Iwo Jima and the ensuing strikes against the Japanese mainland in the spring of 1945. The final, bitterly-won victory at Okinawa was made possible by the relentless operations against the enemy by Task Force 38, of which the Mansfield was a working unit.

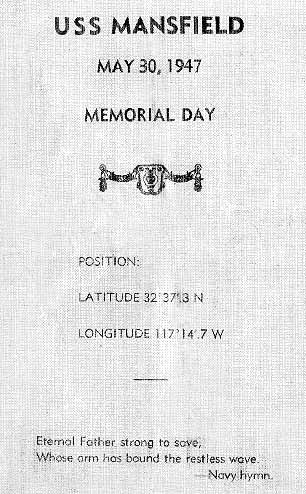

Months of combat cruising, featured by continuous enemy action, was culminated on the night of 22-23 July, 1945, when the Mansfield, in company with eight of her “sisters” of DesRon 61, raced into Sagami Nada, a bay only a few miles south of Tokyo, and delivered a destructive torpedo attack against the enemy’s shipping, sinking two ships, leaving a third afire, and crippling a fourth. On 27 August, in company with the USS Blue, she effected the capture of the Japanese submarine I-400. And finally, on the memorable day of September 7, the Mansfield, joining in the procession of our Pacific Armada, steamed into Tokyo to participate in and witness the Japanese surrender. The road to this victorious day had been tortuous and twisted, one that tested both the abilities of the ship and the men who had so courageously manned her. A raging typhoon that sent three of our destroyers to the bottom and had damaged so many other ships, served only to test her skill and impregnability. Like the countless ships who performed daring, heroic tasks, that had assumed a prosaic insignificance because of their frequency, the Mansfield “had delivered the main”. Months of back-breaking, wearying cruising, highlighted by action with the enemy, had been consummated in the glorious moment of victory that erased ache, pain, and uncertainty. The war had ended, with the cessation of fighting, all eyes looked homeward, all hearts anxiously awaited the long voyage back to the United States. And on that great day of September 1945, almost twelve months after her departure from her homeland, the Mansfield steamed into San Francisco Harbor to share in this city’s tribute to the returning fleet. A few days later the jubilant destroyer moved over to the Mare Island Navy Yard for a much-needed overhaul. By this time, demobilization had become an epidemic disease that threatened the very life of our navy. The ravaging, destructive force of this pestilence had begun to take a strong hold on board the Mansfield. Inside of several months, the once efficient and deadly man-o-war had found herself hopelessly unattended and provided for. Large turnovers of personnel, resulting in insufficient experience and manpower, made conditions critical. The few remaining regulars, and a handful of low-point” reserves, found themselves confronted with a nightmare of obligations and responsibilities. The job of keeping the Mansfield in operation had fallen on their shoulders, that had withstood the burdens and crushing loads of war, and were, by now, weary and eager for rest. The navy yard overhaul ended in late November of 1945, and rumors of impending assignment to duty in Western Pacific waters had already started going around. On December 8, the Mansfield arrived in San Diego and reported for duty. Almost immediately after her arrival, she was ordered to start operating with training units already present there. Six weeks of continuous steaming, broken up by a ten day holiday, passed. On 1 February of 1946, strengthened only by weeks of training before, the Mansfield, with four of the squadron mates, headed west. Honolulu, Eniwetok, and Guam were only stopping-over places. Her destination, China. On February 27, she steamed in the harbor of Tsingtao, China and reported to the Fleet Commander for duty. Six months of duty in China followed, that for one who lived through and experienced them, were as severe and hectic as the war itself. The mission – to meet the commitments of the United States Fleet in Chinese waters. The tools available – a sturdy ship, still in her prime, but manned only with half wartime complement, and the majority of these men, youngsters of only a few months of shipboard experience. The achievement — a mission accomplished. Months of frequent underway periods, roaming up and down the China Coast, from Hong Kong to Taku, up the merciless Yangtze and raging Whangpoo Rivers, over to Jinsen, Korea, and down to Manila. The ship’s roles were many, her superior’s demands heavy, but not once, did she fail to meet an assignment. And from China, the determined Mansfield moved east to Japan to play her part in our navy’s occupational duties. Here again, whether on patrol in the Tsushima Straits, north of Kyushu, or on a flag – displaying visit to Nagoya, Nagasaki, or Fukuoka, she continued her outstanding performance. And each day she trained her men, developed the youngster, who only a few months before required his senior’s watchful eye and guidance. Undermanned, fighting odds that in wartime would have produced fatal results, the Mansfield upheld all the noble traditions she had pursued during the war. To the men who, resolute and loyal, did not falter in their uphill task of making good sailors of their young followers, and to the ship who refused to succumb to any of the forces that constantly threatened her existence, a nation who chose to forget too quickly, should forever owe a debt of gratitude. Today the Mansfield lives and continues to grow stronger. The officers and men who man her are devoted sons, and most of them come to love her during a time of questionable issues and confusing doubts, erupting from this chaotic postwar period. So long as the memory of sacrifice and heroism continues to sanctify the meaning of Memorial Day, ships and men will remember their brothers whose blood has given so rich a color to traditions of the Navy. The Mansfield salutes its fellow warriors who will forever keep vigil in the Pacific. Prayer |

[ Photo Locker ]