50th ANNIVERSARY SALUTE TO THE KOREAN WAR

AUGUST 2000 VOLUME 33, NUMBER 8 by MALCOLM W. CAGLE, CMDR. USN

Page 1  “The Taking of WOLMI-DO”

“The Taking of WOLMI-DO”

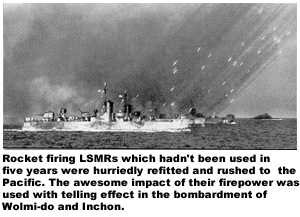

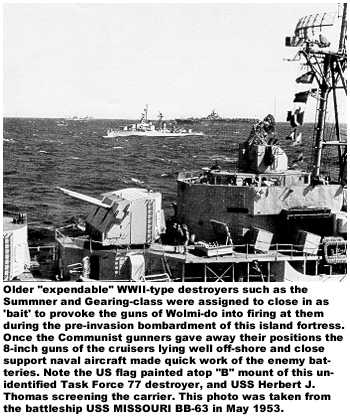

Like a mini-Gibraltar, the heavily fortified islands of Wolmi-do guarding the entrance to Inchon had to be silenced before MacArthur’s amphibious troops could mount their perilous invasion. And no finer sacrificial lambs could lure the fire of the North Koreans better than the reliable WWII-era destroyers of DESRON 9, classified ‘EXPENDABLE’ by the Pentagon.

Koreans have a peaceful and picturesque name for Wolmi-do – Moon Tip Island. The pyramidal hump of land that thrusts 351 feet up from the sea is by far the highest point of land in the Inchon vicinity. Wolmi was the resort area for the sultry, humid seaport. Across its narrow eastern causeway picnickers, swimmers, family parties, and lovers streamed in the summertime.

Koreans have a peaceful and picturesque name for Wolmi-do – Moon Tip Island. The pyramidal hump of land that thrusts 351 feet up from the sea is by far the highest point of land in the Inchon vicinity. Wolmi was the resort area for the sultry, humid seaport. Across its narrow eastern causeway picnickers, swimmers, family parties, and lovers streamed in the summertime.

After South Korea was invaded, Wolmi’s complexion changed abruptly. It became “out of bounds” to the local populace, and the once-placid island vibrated with activity. Trenches were dug; pillboxes built; guns were brought in; barbed wire was strung; mine-fields were planted. Along the southern causeway, which stretched 1,000 yards into the channel, barricades of heavy mesh wire were stretched, supplemented with coils of barbed wire, and every seven feet cast-iron land mines were laid. these deadly cylinders each contained a third of a pound of duPont dynamite. At the end of the causeway, the tiny island of Sowolmi was a nest of harbor defense guns.

In military jargon, Wolmi-do thus “commanded” the sea approaches to Inchon, the harbor, and the beaches. No ship could pass into the port’s tidal basin, the inner harbor, or transit Flying Fish channel without coming under fire of the island’s gun. Like an unsinkable battleship, it stood flay-footedly in the path of any invasion scheme – formidable, deadly, immovable. To capture Inchon first demanded capture or at least neutralization of Wolmi. The Reds calculated their advantages and the enemy’s disadvantages: First, the tides; second, the current; third, the small, winding channel, which would expose them to point-blank enfilade fire; fourth, the water’s lack of depth. Obviously, the Reds concluded, only small ships such as destroyers could get up there, and on their arrival they would be forced to anchor because the current would dash them into the mud. And if they anchored, the destroyers automatically gave up their prime advantages – speed and maneuverability. Such ships would indeed be sitting ducks for Wolmi’s guns. Or so thought the Reds.

“Flying Fish channel was well named,” commented Capt. Norman W. Sears, who commanded the Advance Attack Group that captured Wolmi-do. “A fish almost had to fly to beat the current, and to check his navigation past the mudbanked islands and curves in the channel. Wolmi-do was the whole key to success or failure of the Inchon operation. Admiral Doyle told me that this mission must be successfully completed at any cost; that failure would seriously jeopardize or even prevent the Inchon landing. He emphasized that we had to capture Wolmi no matter what the losses of difficulties.”

Korean weather, like Washington’s, is often unpredictable and usually irascible. Reminding the Inchon planners of its continuing and critical importance, the local weather devil whizzed typhoon “Jane” through Kobe, Japan, on 2 September.

The eye of the typhoon passed the city at 1320, bringing 120-mile-an-hour winds. Pierside ships were wrenched so violently that many parted their cables and were tossed adrift into the crowded harbor. the attack cargo ship WHITESIDE suffered a damaged propeller and a buckled bulwark. The WASHBURN sprung 125 rivets in her engine-room plating. LST-1123, loading Seabee equipment, had a portable pontoon shaken loose.

The Marines, hastily shifting, sorting, and repacking cargo in the reverse order for invasion, saw green water two feet high roll over their stacks of supplies.

From the outer harbor, an emergency message from SS NOONDAY: “Uncontrolled fire in hold three. This hold contains clothing. Adjacent holds two and four contain ammunition. Expedite assistance.” Fire tugs rushed through the boiling harbor to put out the fire.

Jane crossed Japan and disappeared eastward, having succeeded in interrupting a very tight loading schedule for almost 36 hours. This, or any subsequent delay, would not postpone the invasion by hours or days, but a whole month until the next high tide. Neither Inchon’s tight secret nor the weary GIs along the Naktong could hold that long. The loss of a month might mean the loss of the entire campaign. So all hands worked overtime to make up the lost hours, hoping, not unreasonably, that they’d had their typhoon for the season.

But this fervent hope was to be denied. On 6 September, 200 miles west of Saipan, Navy weather men spotted a weak and nearly stationary tropical depression. It might be nothing or it may be the birth of a typhoon.

It was. On 7 September, Navy patrol planes flew out to look at the storm. Now moving northwestward at four knots, the cyclone had ominously intensified. Already the baby typhoon was producing moderate swells along Japan’s east coast. By the next day it had matured to full size and was big enough to warrant a name, “Kezia.” Meteorologists charted the path of the storm and shook their heads. At its present speed and course, it would hit the Korean straits on 12 or 13 September. Winds of 100 miles per hour were already being recorded in Kezia’s core.

On 9 September, the prospect for a collision between Kezia and Joint Task Force 7 seemed unavoidable. Kezia by now was a raving, rampaging 125-mile-an-hour catastrophe heading straight for the invasion staging area.

“by 10 September,” said Adm. Morehouse, “the storm situation had become critical, and in Tokyo we were almost on the ropes with anxiety.”

But the harassed planners of Inchon were to have another headache added to their aching brains the next day. At 0600 that morning, ROK PC boat 703 (Cmdr. Lee Sung Ho), while patrolling north of Inchon Harbor, discovered an enemy boat laying mines. PC-703 fired one round, whereupon the boat disappeared in a big explosion. Intelligence reports were rushed to CINCFE headquarters that Inchon was being mined!

Admiral C. Turner Joy dispatched Admirals Sherman, Radford, and Struble: “The Reds have started mining west-coast Korean ports. So far, efforts are small but believe will accelerate. Recommend high-rate reactivation of minesweepers.”

Admiral C. Turner Joy dispatched Admirals Sherman, Radford, and Struble: “The Reds have started mining west-coast Korean ports. So far, efforts are small but believe will accelerate. Recommend high-rate reactivation of minesweepers.”

If there was ever a good place for mines, V/Adm. Struble observed, Inchon was it. First of all, the muddy water would make mine detection extremely difficult. And, secondly, any ship which struck a mine might block the fleet’s passage up or retirement down, the narrow Flying Fish channel.

Then Kezia commenced a tantalizingly slow curvature to the north on the afternoon of 11 September. If the turn-off continued, there would be no collision of typhoon and task force. Admiral Doyle gambled that the slight right-hand turn was not a feint, and ordered the Transport and Advance Attack Groups to get underway from Kobe and Pusan, respectively, on day ahead of schedule.

Admiral Doyle’s flagship, the USS MOUNT MCKINLEY, cleared Kii Suido the same afternoon and promptly ran into extremely heavy swells, estimated 25 feet from trough to crest. The gamble, nevertheless, paid off, for by the next afternoon all the assault forces had rounded Japan’s southern corner, and had transited the Van Diemen Strait into South Korean waters. Except for three tanks which broke their moorings on various LSTs, only to be quickly rechained, the assault shipping suffered little damage.

The MOUNT MCKINLEY had orders to pick up Gen. MacArthur and his party at Fukuoka, Japan. Kezia diverted the rendezvous to Sasebo and MOUNT MCKINLEY ran before the typhoon two more times – once going in, and again coming out, that landlocked harbor.

Among the recently returned-to-active-duty officers aboard the MOUNT MCKINLEY was Lt. Preston C. Oliver, who only a month before had been enjoying a tranquil civilian life in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

I arrived aboard the MOUNT MCKINLEY late in August, said Lt. Oliver, “and it was immediately apparent that something big was afoot. No one knew what, exactly, but with the many transports and LSTs on hand, plus all the bustle, it had to be something big.

“One morning I looked at the harbor of Kobe and noted that the LSTs had shoved off. This meant that we too would soon be on our way, since the LSTs needed a head start because of their slower speed.

Those first days out of Kobe were rugged the MOUNT MCKINLEY has a lot of topside weight and made the most of every roll in those typhoon-tossed seas. Seasickness became the rule for those long hours and days.

“I had the junior officer bridge watch the night the word came up to change course for Sasebo. That was a surprise to us, bat a bigger surprise was ahead. Sasebo’s smooth waters were a relief, if short-lived, as we went in darken-ship.

“Captain Printup brought the ship alongside quickly and masterfully. The Japanese linehandling crews were standing by to receive our lines, and we made fast and lowered our gangway with unusual speed. A long column of staff cars lined the dock, attended and guarded by snappy Marines. Then Gen. MacArthur strode aboard, followed by his considerable staff; there was a quick transfer of mail, and we were off again.

“Now we knew that Korea would be our next stop. Generals like MacArthur don’t ride ships on typhoon-troubled waters just to kill time. We were on our way.”

Typhoon Kezia was also playing hob with the flattop BOXER, which was frantically trying to make the Inchon deadline. The BOXER‘s deck was jammed with 96 planes ready and eager for the fight; at Pearl Harbor, however, 14 additional spare aircraft had been crammed aboard, destined for the spare aircraft pool at Japan’s Kisaruzu Air Force base. These 14 planes effectively locked the operating deck, and until they could be catapulted clear, Air Group 2’s planes could not operate.

As BOXER neared launching distance of Kisaruzu, the filed set Typhoon Condition II and closed her runways to all traffic. The BOXER swung south, trying to circle around Kezia Clockwise.

“We tried to sneak into Sasebo on the evening of 12 September,” said Capt. Cameron Briggs, “but Kezia got in there ahead of us and was already in the landing circle. We got out of there as fast as we could but not before we had some 80-knot winds.”

“The BOXER fought Kezia all night, and at daybreak launched her 14 spare aircraft for Naha base in Okinawa, 400 miles to the south.

“When we finally did get into Sasebo,” said Capt. Briggs, “we only had a few hours until darkness to load cargo and ammunition, and get underway for Korea. As soon as we hit the pier, Capt. Walter F. Rodee and three members from Adm. Hoskins’s staff came aboard with armfuls of effective operation orders and to brief us. So little time was available that we had to decide whether to read the orders first or to listen to the briefing. We wisely decided to do the latter, although when we finally got time to read the Inchon orders three days after the landing, we found we had unknowingly overlooked many planned details.”

At dusk, 14 September, BOXER slipped out of Sasebo and cranked up full speed for Inchon. The BOXER made the rendezvous, launching her first strike on the afternoon of 15 September. However, just before turning into the wind to launch aircraft, BOXER damaged her number four reduction gear. The rest of her combat was served using only three or her four engines.

At dusk, 14 September, BOXER slipped out of Sasebo and cranked up full speed for Inchon. The BOXER made the rendezvous, launching her first strike on the afternoon of 15 September. However, just before turning into the wind to launch aircraft, BOXER damaged her number four reduction gear. The rest of her combat was served using only three or her four engines.

Red-mustached R/Adm. Higgins had returned aboard the TOLEDO on 8 September, carrying with him the rough plans for the bombardment of Wolmi-do. Immediately, his staff commenced a 72-your marathon to prepare the operation order.

“The intelligence information we had for Wolmi-do,” said Adm. Higgins, “was sufficient to plan the destruction of some guns but the destroyers had to go in there to find new ones and to check the reports on the old ones as well.”

Lieutenant Eugene F. Clark, ensconced on Inchons’s Yong-hung-do, was getting all the information he could and nightly radioing it back to Tokyo.

Report: “A company of North Korean troops are in entrenchments along the sea wall on Inchon tidal basin.”

Report: “tow antiaircraft guns are located on Wolmi adjacent to the former US Communications Building.”

Report: “Wolmi gun defenses consist of three large guns at Sowolmi-do, one gun, size unknown, at south end of breakwater. Four or five machine guns on west side, two on southwest side. Infantry trenches are a few feet back from waterline.”

Report: “There is a gunfire observation post in the tower of a large red building on Wolmi-do.”

Report: “Twenty-five machine guns and five 120mm mortars have been located on Sowolmi-do by observing their fire.”

Report: “Wolmi-do has 20 heavy coastal defense guns placed on island’s seaward side. Extensive concrete trench and tunnel system combs island. Estimated 1,000 troops on island which is restricted; only laborers admitted.”

While Clark was sending in dozens of these reports, Higgins’s staff was plotting the intelligence and discussing how best the strong points could be knocked out.

“One thing we all agreed on,” Adm. Higgins reported, “and that was the desirability of making the attack in broad daylight despite the fact that this forced us to give up the surprise element and made us better targets. But if we went up there at night and hit heavy opposition, there’d be a lot of confusion in that narrow channel.”

The destroyer sailors were anxious not to be worried about colliding with one another, and in case of damage, a daylight tow job would be easier to accomplish than one at night.

“After much discussion about the tides,” said Capt. Halle C. Allan, Jr., Commander Destroyer Squadron 9, “we decided that it would be best for our cans to ride the flooding tide while anchored off Wolmi. this meant that the tide would be coming in, and our destroyers could ride their anchors facing into the current, or out o the harbor. Obviously, this enabled our ships to be headed in the right direction so they could make a quick getaway. There wasn’t any turn-around room around Wolmi.”

“Another reason we chose the flood tide,” added Capt. Paul C. Crosley, Higgins’s chief of staff, “was that it meant the destroyers could ride broadside to the island and bring all ships’ mounts to bear.”

[ Inchon Page ] [ Page 2 ] [ Page 3 ]