50th ANNIVERSARY SALUTE TO THE KOREAN WAR

AUGUST 2000 VOLUME 33, NUMBER 8 by MALCOLM W. CAGLE, CMDR. USN

Page 2  “The Taking of WOLMI-DO”

“The Taking of WOLMI-DO”

The decision to sail into Inchon on a low tide and to arrive just before the flood proved to be a most fortunate choice,” Adm. Higgins emphasized. “In the first place, the presence of mines at Inchon was a surprise to me, although we had accepted them a a calculated risk. By going at it at low tide, lead destroyer MANSFIELD was able to spot a minefield and to avoid it in ample time, because of the low water.

“And in the second place, going in on the low tide meant that we could depress our guns low enough to hit the targets. As it turned out, our guns were barely able to depress low enough to hit some of them. At the peak of a 30-foot high tide, we couldn’t have hit ’em.”

It was decided to leave the four cruisers outside, but close enough to cover the destroyers.

“The restricted waters and the heavy tides,” said Capt. Edward L. Woodyard of USS ROCHESTER, “necessitated that the cruisers remain clear. Most of the cruiser stations were 14,000 yards to 20,000 yards away from Wolmi-do.”

The bombardment plan began to take shape and few changes were made in it. The one major alteration in the bombardment plan – to hit Wolmi for two days, 13 and 14 September, instead of just D-minus-one – was prompted by Clark’s reports of the island’s heavy strength.

“In retrospect,” Capt. Allan reported later, “my destroyers could have silenced Wolmi’s defenses on the morning of 15 September, but of course our losses would have been much greater. even so, we’d have made it stick. The two-day bombardment of Wolmi-do certainly eliminated much of the enemy’s D-day fire.

“I felt we could neutralize Wolmi because of my squadron’s heavy experience along the east coast. they were top-notch gunners and quick on the draw. Even so, we might make some damage, so I took the personal precaution of sending a new set of expensive full-dress clothing home.”

Thus, the six destroyers and four cruisers of Adm. Higgins’s Fire Support Group would start up Flying Fish channel at 0700 on 13 September, the cruisers dropping off some seven to ten miles southwest. As the destroyers neared the island, the planes from Task Force 77’s carriers would conduct an air strike. the destroyers would steam past Wolmi-do, anchor behind some of the guns in a rough semicircle and commence a one-hour bombardment at 1300 – 1:00pm. If the Reds took the bait, the hidden and uncharted guns would open fire on the destroyers and would themselves then be taken under fire. At 1400 the destroyers would steam out of Inchon Bay, covered again by carrier aircraft attacks and the protective fire from the four cruisers.

Which destroyers should be chosen? Destroyer Squadron 9 was the logical choice. They had been in action in Korean waters from the first day. The east-coast blockade had given them ample opportunities to perfect their gunnery. Also, Destroyer Squadron 9 ships were older destroyers with little of the brand-new electronic equipment. If destroyers had to be sacrificed, these older ships were most “expendable.”

Thus, then, the bold yet simple plan for drawing Inchon’s longest fangs.

The early light of 12 September say the gunfire support group sortie from Sasebo. The GURKE detached the same evening to rendezvous briefly with the carrier task force directly west of Kunsan. Task Force 77’s carrier photographic planes had been taking pictures of Wolmi-do all day, and these were now ready for the destroyers. The GURKE rejoined her group next morning just after the ROCHESTER, flying Adm. Struble’s flag, had likewise rendezvoused.

At 0700, 13 September, the task group commenced passage up Flying Fish channel. “There hadn’t been time for rehearsals or preliminary operations,” said Cmdr. Frederick M. Radel, commanding USS GURKE. “About the only preparations we made were to prepare ship for towing, to rig fenders and to get ready for going alongside a damaged or stranded vessel, and to brief and arm repair parties to repel possible boarders.”

The Inchon planners were forced to accept the possibility that a destroyer might go hard and fast aground. In this condition, it was conceivable that enemy troops might try to board. Hence, crews were issued sidearms and rifles, and briefed in the ancient art of repelling boarders.

Most of the destroyer main decks were stacked with extra ammunition – mostly 40mm – the magazines were already full.

Tension mounted as the ships continued up the channel. The Korean interpreter aboard MANSFIELD was turning around the broadcast band when he heard an announcement in his native tongue warning that enemy vessels were steaming toward Inchon, and ordering coastal defense batteries manned.

In Tokyo, meanwhile, an official Communist, dispatch was intercepted. Addressed to Red Headquarters, Pyongyang, it was uncoded and obviously urgent.

“Ten enemy vessels are approaching Inchon,” it read. “Many aircraft are bombing Wolmi-do. There is every indication the enemy will perform a landing. All units under my command are directed to be ready for combat; all units will be stationed in their given positions so that they may throw back enemy forces when they attempt their landing operation.” The dispatch was signed, “From Commanding General.”

The bombing attack mentioned in the dispatch was indeed underway. Of the first group of bombs that struck the island, one chunked into the garrison mess hall just as the noon meal commenced, inflicting many casualties. It was but a taste of the sudden death to come from the destroyers, at that moment relentlessly headed for the island.

In Flying Fish channel, meanwhile, the task group had gone to general quarters as the dark-visaged island of Wolmi rose on the horizon. In single-file column, the destroyers, MANSFIELD, DE HAVEN, SWENSON, COLLETT, GURKE, and HENDERSON, 700 yards between ships, rounded Palmi-do light and turned northward, their four-planed CAP from the PHILIPPINE SEA droning circles overhead.

As the column steamed northward past junks and fishing boats, white-robed spectators thronged the shore of each of the innumerable islands to watch the US Navy steam into battle.

At 1145, 800 yards off the port bow, MANSFIELD’s lookouts spotted what appeared to be a string of mines. Commander Lundgren of DE HAVEN, next in line, announced that it was a minefield. The suspicious objects were barely awash in the muddy, low-tide water. Identification was still uncertain. Anxious binoculars examined the area. From this particular spot, two weeks earlier, the British cruiser JAMAICA had blasted the Inchon coast. Had mines been laid here in anticipation of a return visit?

At 1145, 800 yards off the port bow, MANSFIELD’s lookouts spotted what appeared to be a string of mines. Commander Lundgren of DE HAVEN, next in line, announced that it was a minefield. The suspicious objects were barely awash in the muddy, low-tide water. Identification was still uncertain. Anxious binoculars examined the area. From this particular spot, two weeks earlier, the British cruiser JAMAICA had blasted the Inchon coast. Had mines been laid here in anticipation of a return visit?

There was only one way to find out. The destroyers opened fire. The GURKE’s 40mm mount hit the first mine at 1146 to confirm the suspicions as the sea bomb threw skyward an enormous cascade of water and black smoke.

Captain Allan detached HENDERSON and ordered her to remain temporarily in the vicinity as long as the rising tide allowed to destroy the pestilent mines, and then to rejoin formation at high speed. With the fast-rising tide rushing to cover the exposed mines, only four out of the twelve could be destroyed. But the presence of mines had a t least been confirmed. The big question was, how many more were there?

The other destroyers continued northward and Wolmi’s green-brown hulk was now plainly visible. Still its guns did not speak.

Inchon Harbor was crowded with small craft. The brown sails of 30-odd junks flapped idly in the breeze. From the destroyers’ decks sailors could see idle sunbathers, sportive swimmers, fishermen mending their nets. and townsfolk hurrying to the waterfront to see the parade of warships. It was a curiously unrealistic background to battle.

The destroyers sailed past Wolmi, only 800 yards distant from the hidden guns. The GURKE reached her anchorage first at 1242, and her anchor chain rattled and flashed in the bright sunshine. The HENDERSON, COLLETT, SWENSON, DE HAVEN, and finally MANSFIELD splashed their hooks; the ships rode to a short anchor to be able to move quickly. Navigators took their usual anchoring bearings and recorded them in their logs with the same drab, official phrasing as if another routine anchorage in San Diego Bay had just occurred.

The COLLETT’s log: “1253 Anchored in Flying Fish channel off Inchon Harbor, Korea, with 30 fathoms of chain to starboard anchor, mud bottom.”

For several long minutes the destroyers waited, each flying the prosaic flag hoist “execute assigned mission.” When these flags came fluttering down at 1300, the bombardment would commence.

The minutes crawled by devilishly slow. In the DE HAVEN director Lt. Arthur T. White had his mounts loaded and pointed at a Wolmi Battery. As DE HAVEN had stood up the channel, White had seen North Korean artillerymen scurrying into the gun pits through the magnifying lenses of the range finder. Any second they might fire first.

White called the bridge. “Permission to commence fire?” The answer was “Stand by – our carrier planes are still on target.”

On DE HAVEN’s forecastle, beneath the loaded and ready-to-fire guns of mount number one, two sailors were crawling around on their bellies securing the anchor gear: Chief Boatswains’s Mate Tom A. Lewis and Boatswain’s Mate 2/C Frank l. Jackson. They were the only exposed people forward, unless you could count the several grotesque dummies that had been placed on the forecastle to attract fire. Close up, the dummies were crude affairs, – old dungaree shirts and trousers stuffed with life jackets and rags – but from Wolmi’s distance it was hoped that the Red gunners might be tempted to take potshots and thereby reveal their positions.

At five minutes before 1300, unable to look down the barrels of the Red battery any longer, White’s itching trigger finger depressed the firing key, and the Wolmi bombardment began. The DE HAVEN’s shells were dead-center bull’s-eyes as the Wolmi battery disappeared in a mushroom of dust and debris.

On DE HAVEN’s forecastle, however, the surprise was no less. Chief Lewis and Boatswain Jackson were flattened by the unexpected eruption of two 5-inch guns going off inches above their heads. “I was deaf for two days,” said Chief Lewis.

Several of the dummies on DE HAVEN’s bow were also casualties of the overeager shooting. They caught fire in the muzzle-blast-flame of the first salvo and had to be doused by the Forward Repair Party’s fire hoses.

The other ships opened fire at 1300, slowly at first and with great deliberation. Not a gun had yet fired on them.

The COLLETT’s first target was the large guns at Sowolmi-do. At 1,600 yards range, COLLETT’s first salvos knocked out two of them. One gun was hit directly and the second’s emplacement was destroyed with only 13 rounds.

The SWENSON commenced fire into Red Circle Area Two – this was to be the scene of Red Beach two days later. Directing the fire of the destroyer’s quadruple 40mm mounts was a young officer whose surname by no coincidence at all was the same as the ship’s – Lt. (j.g.) David H. Swenson. The destroyer was named for his uncle, Capt. Lyman K. Swenson, who was lost with his cruiser JUNEAU early in World War II. The Korean War was Dave’s first combat.

At 1303, Capt. Allan radioed Adm. Higgins: “Not even a pistol’s been fired at us yet,” he reported somewhat optimistically. The words were scarcely spoken when Blam! Blam! Blam! – Wolmi’s guns opened fire.

The North Koreans concentrated their fire on the destroyers nearest their guns – SWENSON, COLLETT, and GURKE. The first shells were over, than short. At 1306, six minutes past 1:00 p.m., COLLETT took the first hit. A 75mm shell struck forward on her port side, exploding in the forward crew’s compartment. The damage was not great, but at least one of the Red guns had found the range. Four minutes later COLLETT was hit again, this time by a larger projectile, and right on the waterline. The shell exploded on contact, opening a two-foot hole in COLLETT’s skin, and flooding the stewards’ living compartment with oil and water.

The North Koreans concentrated their fire on the destroyers nearest their guns – SWENSON, COLLETT, and GURKE. The first shells were over, than short. At 1306, six minutes past 1:00 p.m., COLLETT took the first hit. A 75mm shell struck forward on her port side, exploding in the forward crew’s compartment. The damage was not great, but at least one of the Red guns had found the range. Four minutes later COLLETT was hit again, this time by a larger projectile, and right on the waterline. The shell exploded on contact, opening a two-foot hole in COLLETT’s skin, and flooding the stewards’ living compartment with oil and water.

Twenty minutes after the first wound, COLLETT took hit number three, this one in the wardroom. It was a dud shell, which walked through the door, knocked down a shelf of books, dented the opposite steel bulkhead, and fell to rest-on the wardroom sofa.

So far, the three hits received by COLLETT were trivial. No one had been hurt, and the ship was only superficially damaged. Commander Close did not yet see fit to report to Adm. Higgins.

The fourth missile to strike COLLETT, nine minutes later, did more damage that the other three together. The 75mm armor-piercing shell broke into two pieces, on tearing into the fireroom and rupturing a low-pressure air line; the other and larger chunk dug its way into the plotting room, where it broke the firing selector switch of the computer and wounded five men. The COLLETT’s 5-inch guns could no longer be operated by the computer, and control was shifted to each individual mount.

A minute later, COLLETT sustained her fifth hit. None of the other destroyers had been so much as splashed.

“It was obvious by then,” said Cmdr. Close, “that they had my ship boresighted, so I asked Adm. Higgins for permission to get underway and shift my anchorage. At that moment with our guns in local control, we were getting more that we were giving. My request to get underway did not reflect, I hope, any lack of initiative. I simply considered our mission was to locate hidden enemy batteries – and we were doing that maybe too well. At any rate, I asked the permission to shift berths because I felt that a sound decision would be better made by someone with a broader view, as mine was somewhat limited then by the numerous splashes close aboard.”

Destroyer GURKE was next to be taken under fire. At 1330, shells started splashing all around, and it was a seeming miracle that no shell struck her until almost 15 minutes of near misses had covered the ship with sea water. The GURKE also raised her hook to shift her position, but as she did, three shells hit amidships in quick succession. The first one went into the empty gunnery office, holing it in a hundred places, the nose of the shell continuing into sick bay. The second shell hit the ship’s gig; the third holed the smokestack. Damage was not serious and only two men were slightly wounded.

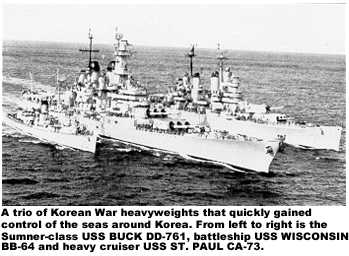

By now, the bombardment of Wolmi was at full fury. The cruisers joined in against the harbor guns as each enemy battery exposed itself. The TOLEDO and ROCHESTER showered 8-inch shells on the fortress, while the 6-inch guns of the British cruisers KENYA and JAMAICA spat incessantly.

At 1400, “the longest hour I have ever lived,” said one sailor, the destroyers moved out of the trap.

“As all ships steamed south of Wolmi-do,” said Cmdr. Edwin H. Headland, Jr., of the MANSFIELD, “each vessel started receiving counterfire from the remaining shore batteries. My ship answered from 3,500 yards with the full battery. Our five-inch salvos landed very close to the enemy guns, but by this time there was so much smoke and dust that visibility was obscured. As we got past Wolmi, and able to fire only our after mount, splashes again started falling around us. I rang up emergency full speed. I distinctly remember seeing on shell pass between my stacks and strike the water 15 yards to starboard.”

[ Inchon Page ] [ Page 1 ] [ Page 3 ]