50th ANNIVERSARY SALUTE TO THE KOREAN WAR

AUGUST 2000 VOLUME 33, NUMBER 8 by MALCOLM W. CAGLE, CMDR. USN

Page 3  “The Taking of WOLMI-DO”

“The Taking of WOLMI-DO”

“In view of the great number of projectiles which landed in out immediate vicinity,” reads COLLETT’s action report, “God must be credited with keeping a watchful and protective eye on us.”

The LYMAN K. SWENSON was not so fortunate. A single enemy shell crashed into the sea near her. Lieutenant (j.g.) David H. Swenson fell dead from a flying fragment, and his assistant, Ens. John M. Noonan, dropped wounded. Swenson’s death was the only casualty of the bold bombardment of Wolmi-do.

The first-inning box score looked good. Only COLLETT’s damage was measurable. The DE HAVEN and GURKE’s wounds were mere scratches, and the death of one man and injuries to eight seemed a mall price for the demolition of Wolmi. Even the wounded could laugh that night, while the destroyers were slowly steaming off Inchon awaiting the morning tide, when the Communist radio at Pyongyang was heard to claim that 13 UN warships had been sunk, or damaged in the battle. Listed by the Reds as sunk were three “small” destroyers, four landing craft, and three barges.

The “sunk” destroyers repeated the Wolmi bombardment at the exact same time the next day. D-minus-one. This time the destroyers would not anchor.

On the return journey up Flying Fish channel, the minefield was sighted again. Admiral Higgins detached COLLETT and fleet tug MATACO and assigned them the duty of destroying the mines. (Five mines were destroyed on D-minus-one.) All ships stopped briefly at 0800 and conducted burial-at-sea services for Lt. (j.g.) David H. Swenson. British flags as well as American flew at half-mast. The Guard of Honor stood by while Marine sentries fired three volleys. Swenson’s body was, in the words of the service, committed to the deep. There was a minute of silent prayer.

On the return journey up Flying Fish channel, the minefield was sighted again. Admiral Higgins detached COLLETT and fleet tug MATACO and assigned them the duty of destroying the mines. (Five mines were destroyed on D-minus-one.) All ships stopped briefly at 0800 and conducted burial-at-sea services for Lt. (j.g.) David H. Swenson. British flags as well as American flew at half-mast. The Guard of Honor stood by while Marine sentries fired three volleys. Swenson’s body was, in the words of the service, committed to the deep. There was a minute of silent prayer.

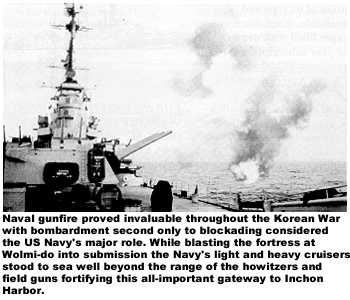

Underway after the short but impressive ceremony the cruisers dropped anchor at 1059, and as the five destroyers (HENDERSON, MANSFIELD, DE HAVEN, SWENSON, GURKE) filed up the channel, the cruisers opened their covering bombardment. Overhead the carrier planes started work again on the island.

Lieutenant Commander Marvin L. Ramsey, flying a VALLEY FORGE Skyraider, gave this description of the island:

“There was a slope leading down to a cove that I had noticed on the first day. It was covered with grass and shrubbery. When I was directed to work the same area over again the second day, every bit of grass was gone and only a few trees remained. The whole island looked like it had been shaved.”

Commander Radel of the GURKE noticed a big difference that second day.

“We fired at Wolmi for a steady 40 minutes,” he said, “before we received any counterfire. even then, the enemy fire was brief, inaccurate and unsuccessful. I only saw two splashes near us, and the closest on was still 200 yards short.”

The destroyers raked the island with methodical, unhurried deliberation. At 1415 and 75 minutes of bombardment, the destroyers moved clear and repassed the shattered island. In an hour and 15 minutes, five destroyers had fired 1,732 5-inch shells into Wolmi and Inchon’s defenses – a better than 50 percent increase over the previous day, and with one less destroyer on the firing line. Best of all, there had been not slightest damage to ships or personnel. And, unlike 13 September, the retiring destroyers left the island silent.

The carrier planes resumed their pasting as the destroyers drew clear. This time, Marine fliers from the jeep carrier BADOEN STRAIT joined in, spotting fire for the still-shooting cruisers.

“When I was circling over Wolmi,” said 1st Lt. Gene Oster, one of the Corsair pilots from VMF-323, “an AA gun opened up on me from the corner of Wolmi. I radioed the gun’s location to the ROCHESTER, and in seconds I saw three quick explosions where that gun used to be.”

“Wolmi was one worthless piece of real estate,” said Marine 1st Lt. Sidney Fisher. “It had been hit so hard and so long with so many things that it looked like it was quivering. I expected it to roll over and sink at any minute.”

Wolmi-do was thus made ready for D-day.

The two-day pounding Wolmi and Inchon had taken must have all but convinced the Reds that the invasion was on its way to that, the most unlikely of targets. But could they be sure? To the north of Inchon, a British task force was hammering Chinnampo. To the south, the harbor of Kunsan was simultaneously under attack: A raiding party had actually landed there the night of 12 September.

The bewildered Communists could not be sure of anything but the undisguisable fact that the invasion was coming. Inchon, they reasoned, might be the diversion and Kunsan the main attack, for their intelligence reports from as far distant as Tokyo declared that Inchon was so freely named in the gossip that it could only be a transparent trick to conceal the real objective.

Planned enemy bewilderment is, of course, a cardinal principle of any amphibious attack. As early as 8 September, Gen. George E. Stratemeyer issued orders to his Fifth Air Force:

“Initiate immediate and increasing intensive bombing and strafing attacks on rail and highway junctions and bridges within 30-mile radius of Kunsan.”

The plans for the hit-and-run amphibious raid on Kunsan were issued the same day from Adm. Joy’s Tokyo headquarters. A miniature but truly unified force was designated – the British frigate HMS WHITESAND BAY (Lt. Cmdr. J.V. Brothers, RN) would carry a mixed British-American force of raiders under command of Col. Louis B. Ely of the United States Army. Part of the order read:

“Conduct beach recon and amphibious landing Kunsan during the period 9-14 September. Purpose of this plan is to obtain essential beach information, to disrupt coastal communications, and to hamper enemy reinforcement in the Kunsan area.”

The on-ship task group left Kobe on Sunday, 10 September, proceeded via the Shimonoseki Strait and arrived off Kunsan on 12 September. Led by Ely, the raiders went in that night and reconnoitered 3,000 yards of the beach and found it unsuitable for a major landing. The raiding party was discovered, however, and was fired upon by machine guns from the northern end of the beach. Two men were lost and one seriously wounded. It was not highly successful in the raider sense, but the fact that troops had tried to get ashore near Kunsan was disturbing to the Reds.

Commander Seventh Fleet also helped perpetuate the deception. The period from 5 September to 13 September was chosen for striking Kunsan both by carrier air strikes and by naval bombardments in an effort, as the order read, to “effect a realistic pattern of preassault softening up to the approaches and defenses of Kunsan. “Struble sent Brothers this dispatch: “Fast carries will strafe beaches and deliver napalm attacks on Kunsan during daylight of 12 September.”

Nature dealt generously with the United Nations forces for the big landing scheduled for the next morning, 15 September. The weatherman made his prediction for D-day: “Typhoon Kezia no longer a threat and no new typhoons brewing. Weather to be clear, visibility at least ten miles, wind six knots from the northeast. Some cloudiness by midmorning and perhaps a moderate squall by late evening.” Generally speaking, predicted the meteorological swami, the next several days looked favorable.

The four ships that were actually to take troops in to capture Wolmi-do were the FORT MARION (LSD-22), the DIACHENKO (APD-123), the HORACE A. BASS (APD-124) and the WANTUCK (APD-125).

The converted destroyer escort HORACE A. BASS embarked Marines on 8 September 1950, in Pusan Harbor.

“In order to accommodate the 289 Marines we jammed aboard,” said Lt. Cmdr. Alan Ray, commanding the BASS “we rigged bunks in the after cargo hold and in our messing spaces. Then we rigged portable blowers for ventilation. In spite of a 100 percent overload of people, we managed to give everybody a bunk and three hot meals a day.

“While waiting to depart Pusan, we conducted two debarkation drills. They proved to be of tremendous value both for the Marines, some of whom had never done it, and for my ship’s company, a lot of whom were new.”

“the FORT MARION was my flagship,” said Capt. Norman W. Sears, “and the Marine team was the 3rd Battalion of the 5th Marine Regiment under the command of Lt. Col. Robert D. Taplett. I ordered the departure from Pusan on 12 September, on day early, because of Kezia, and en route we were escorted by the HMS MOUNTS BAY and the New Zealand ship HMZS PUKAKI, Capt. Unwin, RN, screen commander. We arrived 30 minutes past midnight.”

At a little after 2:30 a.m. the assembled ships assumed their special formation at the entrance to Inchon channel. the long column started out, lead again by MANSFIELD, followed in order by DE HAVEN, SWENSON, DIACHENKO, FORT MARION, WANTUCK, BASS, LSMR-401, LSMR-403, LSMR-404, SOTHERLAND, GURKE, HENDERSON, TOLEDO, ROCHESTER, KENYA, JAMAICA, COLLETT, and MATACO. The group rounded Palmi-do, its light shining brightly in the darkness. Lieutenant Eugene F. Clark, his work done sat atop the lighthouse, watching the ships steam past. Aboard those ships men were eating cold breakfasts at 4:00am – hard-boiled eggs and corned-beef hash. They were blacked-out, but still Clark could see them.

The journey up the mined Flying Fish channel at nighttime was no parade, even if for the destroyers in the column it was the third trip.

The journey up the mined Flying Fish channel at nighttime was no parade, even if for the destroyers in the column it was the third trip.

“there was no moon that night,” said Capt. Sears, “and at first it was as dark as the inside of a cow’s belly. As we stood up the channel, we could smell smoke from the burning area ten miles away. There were fires still burning from the previous bombardments.”

Because of the dangerous navigation conditions in the channel, ” said Maj. Gen. Oliver P. Smith, “the Navy at first wanted to make a daylight approach to Wolmi. But to capture the island we had to land at daybreak. In our early planning, we figured to capture Wolmi by noon, so that by the evening tide we could land a battalion of artillery there and used it in support of the afternoon assault on Inchon. Even so, the two-pronged assault gave the Reds twelve hours to bring up reinforcements. I therefore asked the Navy to make a night approach and land us on Wolmi at daybreak, and they agreed with no protest.”

The skipper of one of the rocket ships, Lt. Frank G. Schettino (commanding officer, LSMR-403), commented about the passage:

“Passage through Flying Fish channel was simplified by our excellent radar performance although we mistook buoys for suicide boats on one occasion. Obviously we couldn’t use our search lights. The numerous islands lining the channel gave a clear presentation on the radar scope so the navigation was relatively simple. The only trouble was the three and on-half know tide and its effect was very noticeable.”

At 5:00 a.m. all ships were in their assigned bombardment stations.

“Before my ships had anchored,” said Capt. Sears, “we received word that some of the Inchon shore batteries covered out southernmost anchorages, so I gave orders to shift all berths northward 800 yards in order to put Wolmi between us and the reported guns.”

The landing force was ordered into the water at 0540, five minutes before the third-day bombardment of Wolmi-do began and 50 minutes ahead of the L-hour schedule for 0630. The BASS, WATUCK, and DIACHENKO discharged their Marines into the waiting 17 LCVP’s. The FORT MARION put three LSUs (each carrying three tanks) into the water. The LCVPs commenced their orbiting circles in the big ships’ lees. In case the mother vessels were damaged or sunk, the Marines would not be lost.

At 0545, the bombardment commenced. The big guns of the TOLEDO roared first, and an 8-inch salvo headed for enemy territory. The Inchon invasion, first phase, was under way.

“The LSMRs [Landing Ship, Medium, Rocket] used in combat at Inchon for the first time amply justified their existence,” said Cmdr . Clarence T. Doss, Jr., Commander LSMR Division 11. “these 200-foot craft were designed to barrage enemy installations with rockets from short range. You might call us the shotguns of a naval bombardment. Those we don’t kill we scare to death.

“At Wolmi, the widely separated targets, all at varying altitudes, gave us a real test. Each rocket ship was equipped with ten continually-fed launchers and during the one day at Inchon the craft fired 6,421 rockets – only 35 of which misfired. We’d have fired more, except that we ran out of the shorter-ranged rockets.”

The LSMRs had other problems. LSMR-403, for example, maneuvered into position between the SWENSON and the circling landing craft ready to fire her first rocket salvo to starboard. But she was three minutes early, for the rocket bombardment was not scheduled to commence until 0615. Against the racing incoming current and despite the use of both engines, Lt. Schettino’s sip dragged anchor northward into the SWENSON’s line of fire.

I had to use full power to get clear,” said Schettino, “and only missed her by ten feet.”

For the next 15 minutes, the box-like ships spewed out the rockets, each on making the sound of a passing express train heard from close aboard. On the beach, the missiles fell like massive raindrops. The concentrated rocket fire was designed to precede the actual beaching of the troops – and it succeeded handily.

“Our rocket coverage was good,” said Doss. “When we opened fire, the target was fairly clear, but by the end, dust and smoke obscured visibility so much, we couldn’t see our hits.”

Actually the visibility had been reduced to less than a hundred yards by the thunderous bombardment. While the smoke made the assessment of damage difficult, it also served to reduce counterfire from the Reds at Inchon. The first wave of LCVPs left the LOD (line of departure) at 0627 1/2 and headed for Green Beach, 900 yards away. It was supposed to be only a three-minute trip, but the first boat did not beach until 0631, one minute late. As the eight LCVPs headed in, picking their way between hulks and wrecks along Green Beach, the carrier planes made strafing pass after strafing pass, lacing the intended landing point with lead.

The sailors and Marines of the force, had they taken note, could have seen many strange scenes in the midst of the noise, confusion, and smoke. White-robed civilians from Inchon, plainly visible, were scurrying out onto the mud flats – obviously an excellent place of refuge, for there were no targets there. One diligent and scared civilian started digging himself a foxhole with his bare hands. Disregarding the shellfire, the harbor became crowded with small boats, each one crammed with refugees – the many small nearby islands offered greater safety than the city. Even to the unbriefed Koreans, it was obvious by now that the pasting Wolmi was getting was much more than another routine naval bombardment. In one of the small boats passing close to MANSFIELD a young Korean mother stood up. She held up her infant baby and yelled something at the destroyer, although the noise of gunfire drowned out her unintelligible words. her meaning, however, was plain and the boat passed safely by, disappearing into the smoke.

At 0631, Wave One landed on Wolmi, scarcely seeing the island until they were hard upon it. The leathernecks tumbled hurriedly inland, past smoking craters left by naval shells and through tree stumps blackened by napalm and splintered by the devastating barrage. The bitter smell of gunpowder – a blend of rotten eggs and ammonia – filled the air.

At 0635, the second wave of Marines was ashore, and ten minutes later, the LSUs bumped onto Green Beach. Their bow doors rattled down, and the tanks rumbled out. Three of the nine carried bulldozing blades for shredding the barbed-and-mesh-wire barriers and for filling in the trenches. Three others carried flame throwers, especially handy for caves and storage pits. Two of the tanks rumbled past a cave and fired two shells into its mouth. Thirty soldiers stumbled out, hands high.

There was surprisingly little resistance – only 17 Marines were wounded from the machine gun and small-arms fire, coming primarily from the Inchon defenses.

Several North Koreans surrendered upon first appearance of the Marines. One group of surprised Marines was treated to a rare surrender scene – a group of six Red soldiers forcing their officer to strip naked and then marching him out to surrender. Others fought to the death, a few leaping into the sea in an attempt to swim to Inchon. Machine gun fire cut them down.

By 0700 Taplett’s battalion was halfway across the island, and one minute later the flag-raising Marines had hoisted Old Glory from the highest point of the island.

One young naval officer almost the first to land on Wolmi-do was Ens. George C. Gilman of the MOUNT MCKINLEY, skipper of an LCVP which took an Advanced Marine Communications team ashore. He also had orders to inquire for any wounded, and to evacuate them.

“I leaped ashore all ready to give battle to any and all North Koreans that just might happen to have slipped by the Marines,” Gilman reminisced. “My enthusiasm was quickly dampened by the fact that my boat had drifted about six feet off the beach and I jumped out into about three feet of water.

“I charged to the beach, though, in the approved style until I noticed that a lot of laughing was going on. A group of Marines were sitting around under a tree that was still standing as if they were enjoying a Sunday-school picnic. So far there hadn’t been any enemy fire.

“I wandered up and down the beach inquiring if there were any wounded. There weren’t any, so I started back to my boat. As I was walking down the beach, a sniper up on the hill opened up on me, a bullet went zinging by and kicked up sand, and I dived for a nearby trench. As I hit it, I came face to face with a North Korean soldier! I grabbed for my gun and was about to open fire when I noticed that his hands were high above his head and that a Marine was standing nearby guarding him and several other prisoners. the Reds were taking their clothes off and when one of them threw his uniform on the ground, I spotted a new looking pair of shoulder boards, so I took out my knife and cut ’em off. The Marine guard remarked that I was worse than the Seabees.

The Marines, after the planting of the Stars and Stripes atop Wolmi, worked their way downhill and southward through the thickets and shale cliffs toward the stubborn promontory of Sowolmi-do.

Here a die-hard group of North Koreans still held out, using their big guns against Wolmi.

On Wolmi’s crest Lt. Col. Taplett talked by VHF radio to Strike Charlie, a flight of eight Marine Corsairs led by Maj. Robert Floeck from the jeep carrier SICILY. Taplett requested that the Sowolmi-do lighthouse area be hit. Floeck’s planes bore down on the area, and five 500-pound bombs and many rockets showered down into the area.

Taplett moved a tank and a rifle squad down the gray stone causeway. There was a brief but vicious fire fight, during which three Marines were badly hit – and then Wolmi resistance collapsed. One hundred and eight enemy troops were dead and 136 had been captured.

At 0807, Taplett radioed the fleet: “Wolmi-do secured.”

[ Inchon Page ] [ Page 1 ] [ Page 2 ]